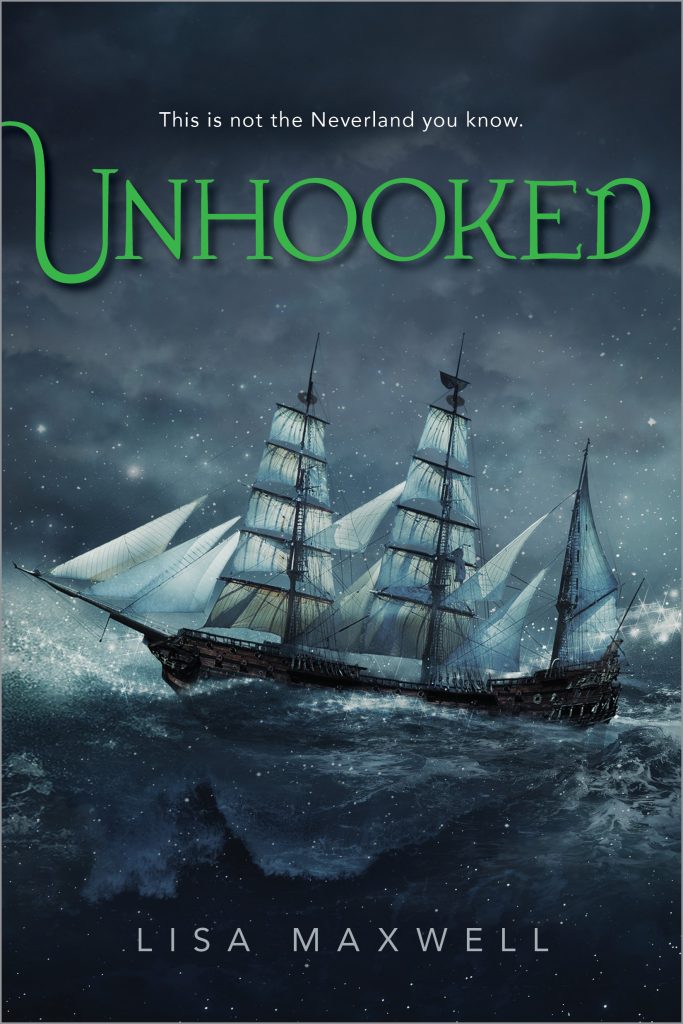

I love Peter Pan, and I especially love a good Peter Pan origin story. It’s safe to say that I’ve seen every adaptation that has been made in the past 30 years or so. Have you seen what the cast of the 1991 Robin Williams film Hook looks like 25 years after its release? I also recently finished reading Lisa Maxwell’s Unhooked, an interesting twist on the Peter Pan origin story.

Both Hook and Unhooked got me thinking about the origins of Peter Pan. The character has existed for more than a hundred years, but where did he come from? What don’t we know about how the boy who never grew up came to be? And what twists and turns did Barrie’s original story take to become what we’re familiar with today?

If you’ve ever seen Finding Neverland, you have some idea, but there’s much more to the story. Here are 12 Peter Pan origin facts you might not already know.

12 Peter Pan Origin Facts You (Probably) Didn’t Know

1. The first time Peter Pan appeared in literature wasn’t in the eponymous Peter Pan.

Little-known Peter Pan origin fact: the first time the world met Peter Pan was in a novel for adults by James (J.M.) Barrie. It was titled The Little White Bird and first published in 1902. It’s fairly dark, but several chapters are lighter in tone. These introduce Peter Pan as a seven day old infant who believes he can fly.

This section of the book received much acclaim, and Barrie realized Peter could be a bigger character. In 1904, he made Peter the focus of his stage play, Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up. In 1906, he published the chapters about Peter as a novel titled Peter Pan in Kensington Garden.

2. J.M. Barrie wrote the play in 1904, but it didn’t appear in print until 1929.

Before Peter got his own novel, Barrie developed a stage play called Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up. The play was produced for the first time on December 27, 1904, and audiences loved it. But Barrie kept tweaking the story after performances, so he waited until 1929 to officially publish it.

3. Part of its initial popularity is because of the Christmas pantomime tradition.

You might not think of Peter Pan as a Christmas story, but in the early years it ran mostly during the holiday season. This is when plays geared towards children based on nursery rhymes and fairly tales were usually produced.

When Peter Pan hit the stage, it was something exciting and entirely new. With flying, fairies, and pirates, it quickly became a popular part of the Christmas tradition in London and New York, and eventually spread around the world.

4. Barrie finally wrote the novel version in 1911.

For many years, everyone knew Peter Pan as a play, but there was no novel version of Peter’s story beyond the chapters mentioned earlier. In 1911, Barrie adapted the play into a novel and called it Peter and Wendy.

5. J. M. Barrie (partially) based the character of Peter Pan on himself.

Peter is a complex character, an amalgam of many people in the author’s life. But to create Peter, Barrie started looked to himself for inspiration, too. Peter is presented as an inadequate outsider in British society, which is how Barrie felt.

One of the biggest similarities is the apparent lack of sexual desire. Wendy wants Peter to act like a father, but Peter literally can’t imagine what it is she wants him to do. Barrie married in 1894 and loved children, but he never had any of his own, though his wife desperately wanted them.

It’s unknown whether Barrie was impotent or just uninterested in sex, but the marriage deteriorated, ending in 1909. In his personal journal Barrie wrote: “Greatest horror—dream I am married—wake up shrieking.” It seems Peter would have the same reaction.

6. He also had his older brother in mind…

The other huge influence on the Peter Pan origin came from Barrie’s older brother, David.

When Barrie was six years old, David died in an ice skating accident two days before his fourteenth birthday. It mystified and disturbed Barrie that, while he would continue to age, his brother never would. People would always remember him as a child. It certainly casts a dark shadow on the phrase “boy who would not grow up.”

Barrie’s brother David wasn’t the only death. His mother had ten children, but by 1929, when Barrie finally published the play, only one of his nine siblings was still alive. The themes of life and death are explored throughout his works.

7. …which got a little weird.

Barrie’s mother openly favored David over all her other children. When David died, James literally tried to fill his brother’s shoes. He would dress up in his brother’s clothes and act like him to try to make his mother happy. Like I said: it was a little weird… but also pretty sad.

8. And then he met the Lleweyn-Davies boys.

These guys, you’ve probably heard of. While walking his dog in Kensington Gardens near his home in London, Barrie struck up a friendship with Sylvia Davies and her five sons: George, Jack, Peter, Michael, and Nico.

Barrie claimed in the introduction to the first print edition of the play that Peter is a result of the boys: “I always knew that I made Peter by rubbing the five of you violently together, as savages with two sticks produce a flame…That is all he is, the spark I got from you.”

His relationship with the family is the subject of many pieces of writing over the decades, as well the film Finding Neverland. While many have speculated over the past hundred years, there’s nothing to suggest he had an inappropriate relationship with the boys.

9. Barrie also really loved the popular adventure novels of his time.

Early 20th century England was really into adventure stories. Robert Lewis Stevenson, a personal friend of Barrie’s, was writing Treasure Island, Barrie was particularly fond of R.M. Ballantyne’s The Coral Island. Society as a whole couldn’t get enough stories about sending ships overseas to “discover” things.

Barrie went so far as to write in Peter and Wendy that Captain Hook was the only person Long John Silver–the main antagonist in Treasure Island–ever feared. When he imagined Neverland, he had all those exploration stories in mind.

10. And then there’s that whole Imperialism thing.

Let’s be honest here: Peter Pan (the story, not necessarily the character) is definitely racist. Barrie took qualities from a bunch of different groups of indigenous people and smashed them together into the Piccaninny tribe.

Disney’s adaptation made them an offensively stereotypical Native American tribe, but in Barrie’s original text it’s not so easy to figure out what he was going for. When Peter Pan debuted, it was the height of the British Empire, so his tribe had features of Australian, North American, Caribbean, and Asian indigenous peoples. The name Piccaninny is derived from the term “pickaninny,” a variation of the Portuguese word pequenino, meaning “tiny”. It was widely used in the UK to describe the indigenous people the Caribbean and Australia, and has come to be understood as an offensive term used to classify any small, dark-skinned child living in a colonized country.

Still not convinced? Let’s look at one of Tiger Lily’s few lines: “Peter Pan save me. Me has velly nice friend.” Yikes. And the Disney adaptation is no better; she got no lines at all.

11. Despite all that, Peter Pan’s legacy has done a lot of good.

When Barrie died, he gave all proceeds from Peter Pan to the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity. To this day, the hospital has a right to royalty in perpetuity in the UK, which means they receive royalties on stage productions, broadcasting and publication of a whole or substantial part of the work, and on adaptations.

Their royalty deal doesn’t apply to derivative works such as sequels, prequels or spin-offs and the copyright has expired everywhere except for the play in the US and Spain. Still, over the years the hospital says it has amounted to a considerable amount of money.

Just how much? As Barrie requested, the hospital has never disclosed the exact amount they have received from his works. Even though the Peter Pan origin is problematic in certain areas (see fact #10), it’s nice to know that its legacy has done a lot of good as well.

12. His story is a favorite for retellings.

While they won’t benefit the Ormond Street Hospital, we’re in the golden age of fairy tale retellings, and the Peter Pan origin seems to be one of the favorites. Over the years there have been countless films, books, plays and cartoons based on the original.

For me, none will come before the incredible Robin Williams/Dustin Hoffman duo in Hook, even if it is over 25 years old. But Unhooked by Lisa Maxwell might be a close second.